A while back I began to notice that my handwriting quality was deteriorating. I was sending too many e-mails and not enough hand-written letters to people. The increasing pressure and speed of life and work pushed me to scribble hasty notes and sometimes illegible memos to myself and others. I didn’t like this one bit. After all, I had spent years practicing calligraphy – the art of fine lettering. Now my penmanship results seemed to be deteriorating. So as a partial remedy, I invested in a nice, $30 Waterman fountain pen. It was an elegant thing, and I made myself write with it for birthday cards and letters to family and friends. I used it to write my shopping lists and notes for stories and articles. This worked to help me slow down enough internally and externally to properly form pleasant, cursive handwriting once again.

A while back I began to notice that my handwriting quality was deteriorating. I was sending too many e-mails and not enough hand-written letters to people. The increasing pressure and speed of life and work pushed me to scribble hasty notes and sometimes illegible memos to myself and others. I didn’t like this one bit. After all, I had spent years practicing calligraphy – the art of fine lettering. Now my penmanship results seemed to be deteriorating. So as a partial remedy, I invested in a nice, $30 Waterman fountain pen. It was an elegant thing, and I made myself write with it for birthday cards and letters to family and friends. I used it to write my shopping lists and notes for stories and articles. This worked to help me slow down enough internally and externally to properly form pleasant, cursive handwriting once again.

In the same way, a journal of daily thoughts and observations about nature and life can help you to develop stronger observation skills, and build an archive of observations that tells an intimate story of nature through the seasons.

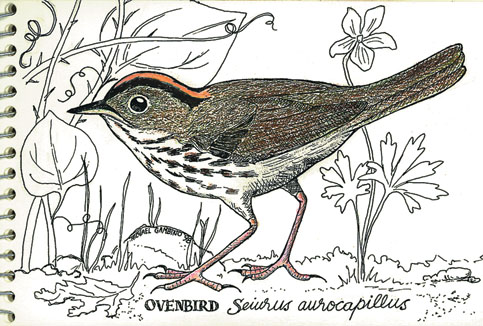

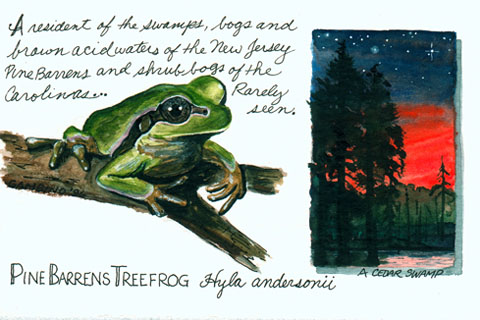

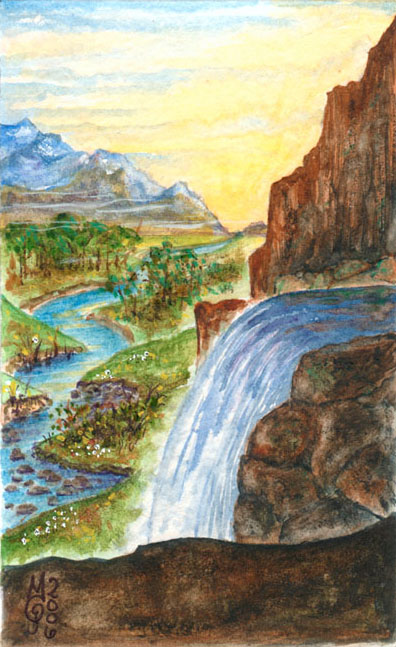

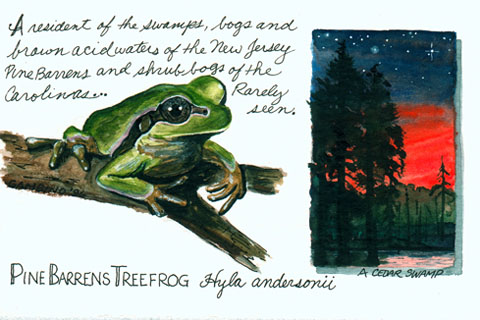

There is no right or wrong way to keep a journal, so I will just cover a few points about them in an effort to encourage you to take up the fine art of nature journaling. You don’t have to be artistic to draw a pine cone or a leaf or a beetle or a flower onto the pages that await you. Just keep at it. The main benefit of drawing is that is challenges you to really observe what is in front of you and not rush ahead filling in the details from your imagination. If you absolutely do not want to draw, take a digital photo of such things and insert a print into your journal. Be sure to include your observations along side. Remember that there are many famous diaries and sketch books in museums around the world. They are a glimpse into the past, a record of the process and progress of ideas and projects, and of important events. You might want to hand your finished journal to your grandchildren one day. Imagine if you had been given such a journal or diary written by the hand of one of your distant relatives? What a treasure that would be!

There is no right or wrong way to keep a journal, so I will just cover a few points about them in an effort to encourage you to take up the fine art of nature journaling. You don’t have to be artistic to draw a pine cone or a leaf or a beetle or a flower onto the pages that await you. Just keep at it. The main benefit of drawing is that is challenges you to really observe what is in front of you and not rush ahead filling in the details from your imagination. If you absolutely do not want to draw, take a digital photo of such things and insert a print into your journal. Be sure to include your observations along side. Remember that there are many famous diaries and sketch books in museums around the world. They are a glimpse into the past, a record of the process and progress of ideas and projects, and of important events. You might want to hand your finished journal to your grandchildren one day. Imagine if you had been given such a journal or diary written by the hand of one of your distant relatives? What a treasure that would be!

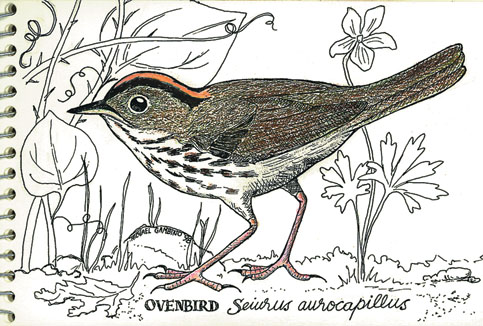

First of all, I would like to say a word about seeing. Looking and seeing are not the same thing. It may seem so at first, but think about it – you can look at a dandelion and still not see how many leaves, petals, seeds, or tiny hairs it has. How many wings does a butterfly have? It may look like they have two wings, but by observing carefully you will see they have four! Some birds hop on the ground while others walk, but do you know why? Keeping a daily nature journal can help you answer this and many other questions about the world outside while your journal becomes a unique work of art.

First of all, I would like to say a word about seeing. Looking and seeing are not the same thing. It may seem so at first, but think about it – you can look at a dandelion and still not see how many leaves, petals, seeds, or tiny hairs it has. How many wings does a butterfly have? It may look like they have two wings, but by observing carefully you will see they have four! Some birds hop on the ground while others walk, but do you know why? Keeping a daily nature journal can help you answer this and many other questions about the world outside while your journal becomes a unique work of art.

Traveling no further than your own backyard, local park, lake, or seashore, you can discover which animals use these spaces as their home, grocery store, or a place to raise their young. You can watch plants grow, and observe the fascinating life-cycle of insects. Above all, you will begin to see that everything has a unique place and purpose in nature. Make your notes, and have your field guides ready at home or on hand to look up your discoveries.

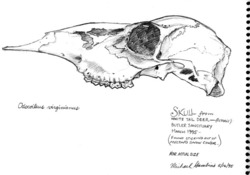

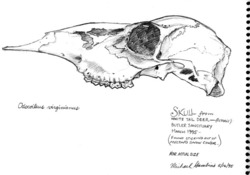

Try still-life or object studies to improve your observation and drawing skills. A found skull or other bone, a flower, a hickory nut, an interesting leaf shape, feathers, an old nail in a fencepost – anything will become interesting once you start to look for its unique qualities.

There are a few tools you’ll need to get started. Buy or make a sturdy journal with blank pages so you can sketch what you see and write down your comments, questions, and discoveries. Size is up to you. You can find these wherever you buy school or art supplies. You’ll need a regular pencil for drawing and writing, and may want colored pencils as well. Clear tape will be handy for attaching interesting bits of bark, leaves, feathers, and photos to your journal pages. A hand magnifying lens will get you closer to your subject to view more details, and a ruler helps your accuracy when recording the size of your subject. If you are more than a few minutes from home, be sure to pack a snack and some water along with a rain jacket. A plastic zip-close bag can hold your journal and camera and other stuff on rainy days.

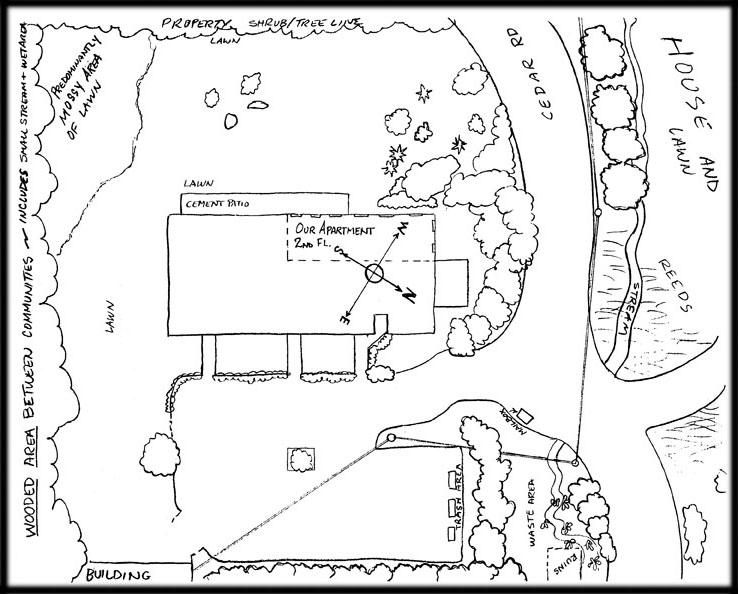

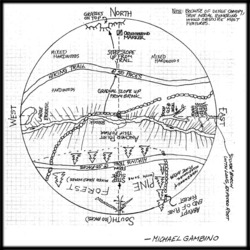

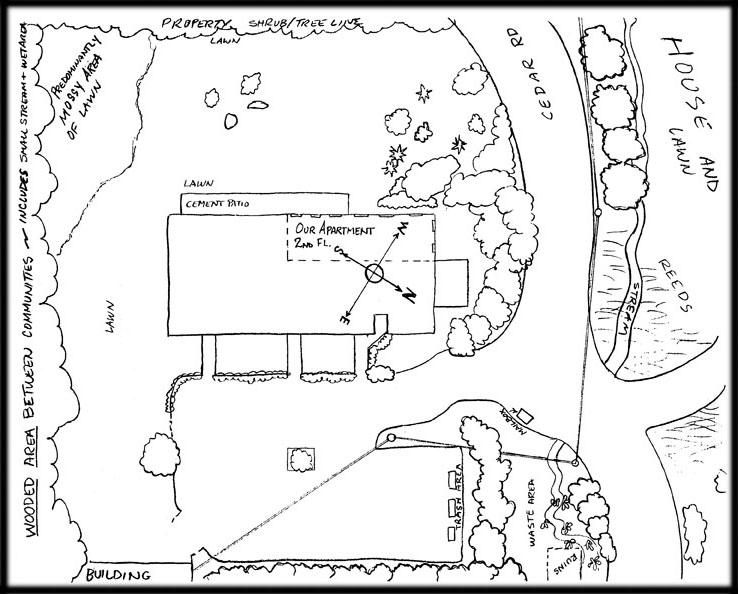

Arriving at your chosen site, look around and draw a simple map of your study area. Try to imagine how it would look to a bird flying over head. You don’t even have to travel further than the area around your home. Draw in fences, driveways, shrubs, utility poles, the garage, vehicles, shed, flower beds, stone walls, and any other features that are present. Mark them down using simple geometric and blob-shapes – don’t worry about your drawing skills. Just indicate where things are in relation to each other. Find out which way is north (the red arrow on a compass points north) and note it on your map. Now, when you fill in your journal pages, be sure to make references to your map noting where you made each new discovery.

Arriving at your chosen site, look around and draw a simple map of your study area. Try to imagine how it would look to a bird flying over head. You don’t even have to travel further than the area around your home. Draw in fences, driveways, shrubs, utility poles, the garage, vehicles, shed, flower beds, stone walls, and any other features that are present. Mark them down using simple geometric and blob-shapes – don’t worry about your drawing skills. Just indicate where things are in relation to each other. Find out which way is north (the red arrow on a compass points north) and note it on your map. Now, when you fill in your journal pages, be sure to make references to your map noting where you made each new discovery.

Find a spot in your study area that catches your interest. You will likely be the first person to really see what’s there! An area with a diversity of plants is a good place to start because a variety of plants often means that a variety of animals may use the area for shelter or for obtaining food. Don’t be concerned if you don’t have a lot of land to explore – that’s part of your expedition – to find out what exists in even the smallest patches of earth. Here are some suggestions for backyard type places: grassy areas where the lawnmower blades can’t reach, sandy areas, rock piles, under and around household objects, fences, hedgerows, wet places, shady spots, and sunny areas.

Many creatures need to stay moist and cool. Too much sun would dry them out, so they stay down close to the soil or hide underneath leaves. Carefully part the grasses and leaves and you’ll see what’s going on down there. A magnifier can help you find teensy bits of chewed seeds, insects or insect parts, animal tracks, fungus roots, mouse hair, or miniature plants. You will also see what soil is really made of (and it’s not “dirt”).

Many creatures need to stay moist and cool. Too much sun would dry them out, so they stay down close to the soil or hide underneath leaves. Carefully part the grasses and leaves and you’ll see what’s going on down there. A magnifier can help you find teensy bits of chewed seeds, insects or insect parts, animal tracks, fungus roots, mouse hair, or miniature plants. You will also see what soil is really made of (and it’s not “dirt”).

Like a detective solving a puzzle, begin asking yourself questions about what you see. “What happened here? What is this telling me? What can I learn from this?” This helps to direct your attention and focus the mind. You may not know the names of trees or plants or insects, but you can certainly describe what you see. For example, reading this description: “a small insect about the size of a pea, black head, red-orange body with nine black spots on back, short legs, very shiny and smooth, found on a tomato plant”, you would probably guess correctly that it was the familiar Ladybug. Once you get a good description down in your journal, using a field guide can help you identify plants and animals and learn about their official names, habitats, and behavior.

Also on your journal pages include the time of day you are making your observation and what the weather was like. If you keep your journal for a full year cycle, you can anticipate for next year when certain plants flower, when bird species arrive in the spring or depart for the winter.

Try to spend at least 15 minutes each time you journal, and vary the time of day to see what takes place during the morning, afternoon, and evening. Sometimes it’s best just to sit still and watch carefully. That’s how you’ll realize things like larger birds, such as pigeons, crows, and turkeys walk rather than hop because they spend most of their time searching for food on the ground. Smaller birds, like chickadees and finches, spend more time amongst the safe tangle of branches in trees and shrubs where hopping is a more effective way of getting around.

Try to spend at least 15 minutes each time you journal, and vary the time of day to see what takes place during the morning, afternoon, and evening. Sometimes it’s best just to sit still and watch carefully. That’s how you’ll realize things like larger birds, such as pigeons, crows, and turkeys walk rather than hop because they spend most of their time searching for food on the ground. Smaller birds, like chickadees and finches, spend more time amongst the safe tangle of branches in trees and shrubs where hopping is a more effective way of getting around.

Don’t let the weather deter you too often – there is a world of beauty waiting for you out there in the rain when everyone else is indoors. On days like that, you may choose to make journal entries once you’re back at home where it is dry.

With regular attention, your nature journal can become an exciting record of your discovery of the unique nature of your backyard – or anyplace you travel.

Tuesday, April 27, 2010 at 06:07PM

Tuesday, April 27, 2010 at 06:07PM